This piece appeared on Citizens for a Thriving Windsor's website on Dec. 10, 2025

Governor Lamont signed House Bill 8002 into law. If you are interested in the details, I would point you to Ginny Monk’s work at the CT Mirror. She has done excellent reporting on this bill throughout its tumultuous history.

While this bill is a milestone for Connecticut, it is less than what is needed. It eliminates the “fair share” portion of the original bill and replaces it with “housing growth plans.” In effect, Lamont vetoed the stick and agreed to the carrot. This is likely to leave zoning unaddressed in many areas of the state with high demand and underutilized capacity for additional housing.

Windsor

The bill is unlikely to have much of an impact on Windsor for two reasons. First is the good news: as a town, we are already making strides towards denser housing near transit. There’s always room for improvement, but Windsor’s political leadership and town staff are making a good-faith effort to address housing in town, and it shows.

Unfortunately, the second reason somewhat counteracts the first. The housing market is not confined to town or state borders. Towns in the same region with strict and permissive zoning suffer the same high housing costs. This bill is a good start, but it doesn’t address the underlying problem: many towns are unwilling to allow housing growth and there is little political will in the state to make them change.

On the plus side, this bill moves the state toward regional and state-wide housing planning. There are still incentives for towns to allow more housing near train and bus stations, “Work, Live, Ride.” There are still provisions for towns participating in Work, Live, Ride to allow conversion of commercial properties to residential. It continues to waive off-street parking requirements for new development up to 16 units. It’s not perfect, it’s not enough, but it’s a step in the right direction.

Anger

Watching the debate in the General Assembly, the anger of the opposition was palpable. Unusually for Connecticut legislative sessions, opponents could not resist casting aspersions on the motives of the bill’s authors. They insisted they were ignored in the process, a pretty jarring claim given that the governor had vetoed a similar bill in response to their criticism.

What’s the disconnect? Why does the number of parking spots in new developments cause such a strong response? Why does the political party of business and cutting red tape bristle at allowing property owners to develop their land with less government intervention? Why the seething anger?

History

Escaping the Depression

It’s worth considering how we got here. The modern housing economy has its roots in the Great Depression. In order to avert a deflationary spiral, the federal government began guaranteeing loans. It didn’t take long for the 30-year mortgage to develop, something that local banks could never have offered previously at a reasonable interest rate. This stabilized the housing market during the Depression by artificially increasing demand through government-backed loans. This process also created a secondary market for the debt of these new mortgages, which began the process of financializing housing. The wealth created from housing debt began to spread throughout the entire economy.

There was real fear after WWII that the country would slide back into the Depression as the country unwound the war economy. To stave off this possibility, and to provide a benefit to vets returning from overseas, new borrowing instruments were created to allow veterans to buy homes with much lower down payments and interest rates. The boom in housing construction in the suburbs fueled private sector growth. Cars enabled low-density suburbs to function and provided a product for industries transitioning from war-time manufacturing. The federal government continued to facilitate this transformation through enormous road construction projects, which helped soften the blow of post-war spending reductions.

Entire neighborhoods were built to a “finished state” with all the amenities of the modern nuclear family could possibly need within a short distance… provided you purchased a self-propelled vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine.

A New Way of Life

It’s hard to overstate how radical a departure this was from the ad hoc way towns and cities had developed for millennia. The effect was the aesthetic of small town republicanism without the actual rural economy. Money had to be made somewhere else and brought home to the suburbs. The newness and uniformity gave a sense of social and economic order that would reify the country’s social hierarchy, maintain the astonishing post-war prosperity, and defeat those godless commie bums through the might of our productivity and consumption. The overarching financial system was largely invisible to most people, in part due to its enormous complexity. Someone taking out a small business loan may well be indirectly borrowing from capital that was backed by their own mortgage debt. All of this was opaque to most people.

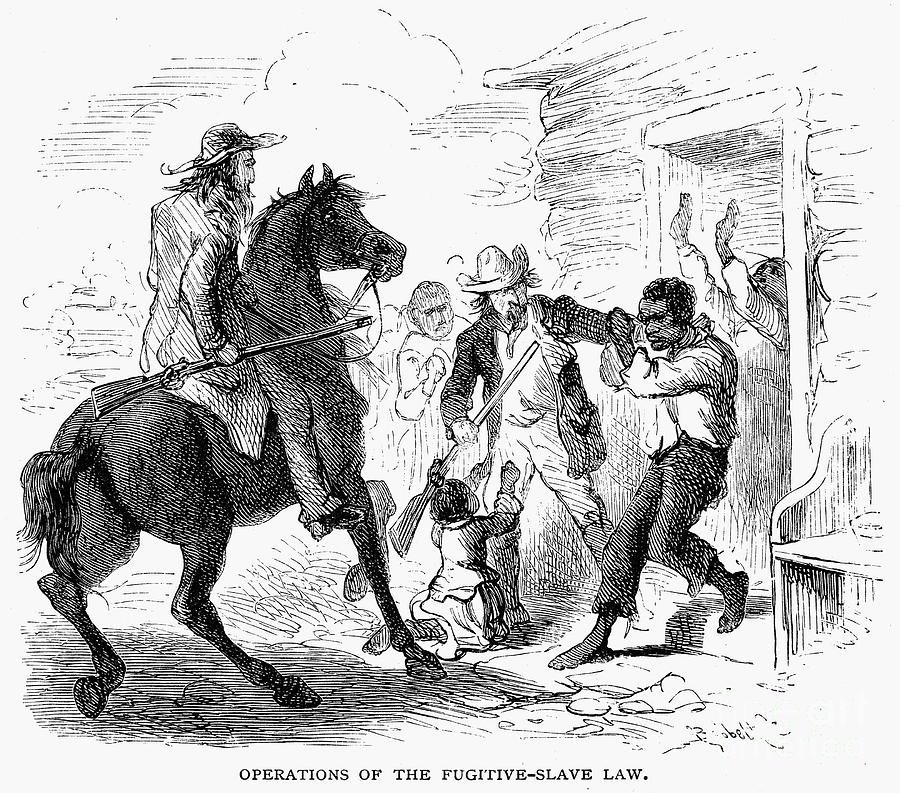

The new developments reflected the biases and prejudices of the society that created them. Many of the veteran benefits and financial instruments that helped fund suburban expansion were unavailable to women and minorities. The racial makeup of Hartford and surrounding towns is still heavily influenced by the red lines banks drew on maps denoting areas for “undesirables.” In these areas, loans would be issued at significantly higher interest rates, or denied entirely.

Towns competed for wealthier residents by zoning larger minimum sizes for lots, on the theory that this would increase the value-per-acre of land while also supporting services for fewer residents. The opposite has been the case; less dense development requires more utilities per taxpayer, and especially more services for housing types that attract families with school-aged children. The maintenance on these systems has become ever more expensive. Most towns now balance their budgets via deferred maintenance and external revenue from state and federal funding. Put another way, while most towns maintain a balanced annual budget, they don’t actually have the tax base to maintain the infrastructure they’ve built.

Multiple generations (mine included) grew up under this system with an unquestioning belief in suburban, car-based development as the guarantor of American prosperity. A house and a garage on a half-acre symbolized financial independence, stability, and a store of wealth to pass on to future generations. Cars became the embodiment of American individualism and the triumph of our ingenuity as a free people. The American identity became wrapped up in this development pattern as a way of life. It was, and still is, viewed by many as an unalloyed good.

Reevaluating

However, many people’s faith in this system has been shaken over the past two decades. The 2008 financial crash revealed how fragile the system is, and showed that taxpayers would carry the burden of this fragility. Over time, exclusionary zoning and subsidized credit slowly reduced housing supply and increased demand, thus raising prices. Those higher prices produced more debt as buyers stretched further to meet escalating prices.

Ownership of that debt created wealth that could be leveraged into all facets of the economy. And what if the loans that kept the whole system afloat were bad? We found out in 2008: our leaders decided it was better for the American public to bail out the lenders than to deal with the underlying causes of both the financial crisis and the housing shortage. A drop in housing prices now posed a risk to the entire economy.

But many have not shaken their faith in this system. They are convinced of the inherent goodness of suburban land use, or at least the aesthetics of the time period when the suburbs were built. They view cars and car ownership as drivers of prosperity. And they view any change to this system as deeply threatening. While this reaction can be baffling when the topic is something as seemingly technical as lane widths, if you consider the assumptions that go into the suburban mindset then you begin to see what is at stake for people who believe in this system; this development pattern is viewed as the substratum of the order, prosperity, and socioeconomic status that gives dignity to our lives. If we bear this in mind, we begin to glimpse some people’s deep attachment to the status quo, and their anger at anyone who might try to change it.

Proposed Solutions

What Doesn’t Work

Thus, many policy proposals to address the housing crisis are designed more to save the status quo than to address the underlying problems. A few that come up with some regularity:

Insert money at the point of purchase – Trump’s 50-year mortgage proposal and Kamala Harris’s $25K in downpayment support for first-time homebuyers have something in common: they both increase purchasing power (demand) without increasing supply, thus raising prices. Ironically, this inflationary pressure would be most acutely felt in the types of housing units needed by the types of borrowers these policies target; that is, starter homes and small family units. Put another way, these policies put upward price pressure on exactly the type of housing we need as affordable housing.

Public housing – I have yet to see a public housing proposal that details exactly how this type of housing would be built, where it would be built, and how it would be funded, so it would be unfair to pass judgement on whether a public housing plan could work. However, I do think it’s worth considering the government’s role in the housing market if public housing were to become the main method of dealing with the housing shortage. Public housing absent zoning and finance reforms is essentially the government saying it is going to keep restrictive housing policies while also deciding what and where new housing gets built to make up for the shortfall in supply. This is tiptoeing very close to a command economy. Given the scale of the crisis, I understand the impulse, and I can imagine a role for public housing in specific circumstances. But, in general, I would be hesitant to trust the entity largely responsible for creating the problem with solving it.

Build baby build – Should we continue to sprawl? The argument is tempting; if the problem is low supply, let’s make more. We know how to build greenfield housing, so let’s do it! The problem is the tax density issue I mentioned earlier. Single-family, 1/4 to 1 acre development alone is not financially sustainable in the long run. The infrastructure required to run a town that is developed on this model is more expensive than towns can charge in property taxes, so they rely on state & federal funds to make up the gap. Complete local self-sufficiency is neither practical nor desirable, but there must be financial stability somewhere in the system. If a development model results in the vast majority of towns not being financially solvent in the long term, then the development pattern doesn’t work. We need to build self-sustaining places that can then create the economic activity that sustains the less dense places nearby.

Moving Forward

So, how do we solve these interlocking problems? We can’t start over, and the suburbs aren’t going away. What do we do?

Very smart people have been thinking about this much longer than I have. Strong Towns has compiled a list of housing-ready policies that will help create density in existing neighborhoods, thereby making them more financially sustainable, while creating local jobs in the form of small-scale housing projects.

1. Allow conversions from single-family to duplex or triplex by right.

2. Permit backyard cottages in residential zones.

3. Legalize starter homes in all residential zones.

4. Eliminate minimum lot sizes in existing neighborhoods.

5. Repeal parking mandates for housing

6. Streamline approvals and permitting.

These policies are not a silver bullet, and local variation is likely needed. But they are more likely to work than the previously mentioned proposals because they allow us, homeowners and neighbors, to make decisions with our knowledge of local needs and the local market, all while catalyzing the local economy with small, locally-financed projects that employ local craftspeople.

In addition, Strong Towns founder Chuck Marohn makes a compelling case that local government has a role to play in plugging the financing gap for housing projects that traditional banks won’t provide loans for; things like incremental home projects, or building a backyard cottage, or an addition for a relative.

And then there’s the issue of how to talk about these necessary changes. We should be clear about our priorities, the facts, and the history that got us here. We need to remind ourselves that the wider audience does not spend much time thinking about these issues. They are trying to understand these very complex ideas while holding the same assumptions most of us held at one time or another.

These are generational problems that will not be solved with one bill. They require questioning the status quo while simultaneously taking the time to understand its intricacies. There is a way out of the housing crisis, but we need to stare the problem directly in the face. We need both practical optimism and radical common sense.